Immune-based therapy under evaluation for treatment of covid-19

Содержание:

- What to do if you’re sick

- Recovering from COVID-19

- Clinical Presentation

- What is the 2019 coronavirus?

- Anti-Interleukin-6 Monoclonal Antibody

- Vaccines

- Abstract

- Asymptomatic or Presymptomatic Infection

- How are coronaviruses diagnosed?

- Mild Illness

- Acknowledgments

- Neuromuscular Blockade in Mechanically Ventilated Adults With Moderate to Severe Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome

- Mechanically Ventilated Adults

- Cited by 1,380 articles

- What are the other types of coronaviruses?

- Thromboembolic Events and COVID-19

- References

- Regaining Your Strength After Severe Illness

- General Prevention Measures

- Panel Composition

- Development of the Guidelines

- What is COVID-19?

What to do if you’re sick

, follow the steps below to care for yourself and to help protect other people in your home and community.

- Stay home. Most people with COVID-19 will have only mild illness and can recover at home without medical care. Do not leave your home, except to get medical care. Do not visit public areas.

- Take care of yourself. Get rest and stay hydrated. Take over-the-counter medicines, such as acetaminophen, to help you feel better.

- Stay in touch with your doctor. Call before you seek medical care. Be sure to get care if you have trouble breathing, have any other , or if you think it is an .

If you have these emergency warning signs, call 911.

Recovering from COVID-19

When to discontinue home isolation. If you have stayed home due to illness from confirmed or suspected COVID-19 you should follow the guidance of your healthcare provider and local health department on when to end home isolation. Multiple factors are taken into account in determining when it is safe for you to return to work or emerge from self-quarantine. For instance, longer periods of home isolation may be recommended for individuals who are severely immunocompromised.

In most cases, your doctor will make one of the following recommendations based on your circumstances:

| Experiencing Symptoms | No Symptoms (Asymptomatic) | |

|---|---|---|

| Viral tested for current infection | Stay home, and distanced from others, for at least ten days since the symptoms first appeared, fever has been gone at least 24 hours without using fever reducing medications and with improvement of other symptoms. | Stay home, and distanced from others, for at least ten days since the viral test came back positive. Monitor yourself for symptoms. |

| Not viral tested for current infection or haven’t received results | Stay home, and distanced from others, for at least ten days since the symptoms first appeared, fever has been gone at least 24 hours without using fever reducing medications and with improvement of other symptoms. | Stay home, and distanced from others, for at least 14 days.*This scenario assumes you have been potentially exposed to the virus and are isolating to prevent the possible spread of infection. |

Clinical Presentation

The estimated incubation period for COVID-19 is up to 14 days from the time of exposure, with a median incubation period of 4 to 5 days.6,18,19 The spectrum of illness can range from asymptomatic infection to severe pneumonia with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and death. Among 72,314 persons with COVID-19 in China, 81% of cases were reported to be mild (defined in this study as no pneumonia or mild pneumonia), 14% were severe (defined as dyspnea, respiratory frequency ≥30 breaths/min, saturation of oxygen [SpO2] ≤93%, a ratio of arterial partial pressure of oxygen to fraction of inspired oxygen [PaO2/FiO2] <300 mm Hg, and/or lung infiltrates >50% within 24 to 48 hours), and 5% were critical (defined as respiratory failure, septic shock, and/or multiorgan dysfunction or failure).20 In a report on more than 370,000 confirmed COVID-19 cases with reported symptoms in the United States, 70% of patients experienced fever, cough, or shortness of breath, 36% had muscle aches, and 34% reported headaches.3 Other reported symptoms have included, but are not limited to, diarrhea, dizziness, rhinorrhea, anosmia, dysgeusia, sore throat, abdominal pain, anorexia, and vomiting.

The abnormalities seen in chest X-rays vary, but bilateral multifocal opacities are the most common. The abnormalities seen in computed tomography of the chest also vary, but the most common are bilateral peripheral ground-glass opacities, with areas of consolidation developing later in the clinical course.21 Imaging may be normal early in infection and can be abnormal in the absence of symptoms.21

Common laboratory findings in patients with COVID-19 include leukopenia and lymphopenia. Other laboratory abnormalities have included elevated levels of aminotransferase, C-reactive protein, D-dimer, ferritin, and lactate dehydrogenase.

While COVID-19 is primarily a pulmonary disease, emerging data suggest that it also leads to cardiac,22,23 dermatologic,24 hematological,25 hepatic,26 neurological,27,28 renal,29,30 and other complications. Thromboembolic events also occur in patients with COVID-19, with the highest risk occurring in critically ill patients.31

The long-term sequelae of COVID-19 survivors are currently unknown. Persistent symptoms after recovery from acute COVID-19 have been described (see Clinical Spectrum of SARS-CoV-2 Infection). Lastly, SARS-CoV-2 infection has been associated with a potentially severe inflammatory syndrome in children (multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, or MIS-C).32,33 Please see Special Considerations in Children for more information.

In early 2020, a new virus began generating headlines all over the world because of the unprecedented speed of its transmission.

Its origins have been traced to a food market in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. From there, it’s reached countries as distant as the United States and the Philippines.

The virus (officially named SARS-CoV-2) has been responsible for millions of infections globally, causing hundreds of thousands of deaths. The United States is the country most affected.

The disease caused by an infection with SARS-CoV-2 is called COVID-19, which stands for coronavirus disease 2019.

In spite of the global panic in the news about this virus, you’re unlikely to contract SARS-CoV-2 unless you’ve been in contact with someone who has a SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Let’s bust some myths.

Read on to learn:

- how this coronavirus is transmitted

- how it’s similar to and different from other coronaviruses

- how to prevent transmitting it to others if you suspect you’ve contracted this virus

Anti-Interleukin-6 Monoclonal Antibody

Siltuximab

Siltuximab is a recombinant human-mouse chimeric monoclonal antibody that binds IL-6 and is approved by the FDA for use in patients with Castleman’s disease. Siltuximab prevents the binding of IL-6 to both soluble and membrane-bound IL-6 receptors, inhibiting IL-6 signaling. Siltuximab is dosed as an IV infusion.

Clinical Data for COVID-19

There are limited, unpublished data describing the efficacy of siltuximab in patients with COVID-19.11 There are no data describing clinical experiences using siltuximab for patients with other novel coronavirus infections (i.e., severe acute respiratory syndrome , Middle East respiratory syndrome ).

Adverse Effects

The primary adverse effects reported for siltuximab have been related to rash. Additional adverse effects (e.g., serious bacterial infections) have been reported only with long-term dosing of siltuximab once every 3 weeks.

Considerations in Pregnancy

There are insufficient data to determine whether there is a drug-associated risk for major birth defects or miscarriage. Monoclonal antibodies are transported across the placenta as pregnancy progresses (with greatest transfer during the third trimester) and may affect immune responses in utero in the exposed fetus.

Vaccines

Vaccines for SARS-CoV-2 are aggressively being pursued. Vaccine development is typically a lengthy process, often requiring multiple candidates before one proves to be safe and effective. To address the current pandemic, several platforms are being used to develop candidate vaccines for Phase 1 and 2 trials; those that show promise are rapidly moving into Phase 3 trials. Several standard platforms, such as inactivated vaccines, live-attenuated vaccines, and protein subunit vaccines, are being pursued. Some novel approaches are being investigated, including DNA-based and RNA-based strategies and replicating and nonreplicating vector strategies, with the hope of identifying a safe and effective SARS-CoV-2 vaccine that can be used in the near future.4,5 Phase 3 clinical trial data are available for two candidate vaccines. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for one of the vaccines and is discussing a possible EUA for the other vaccine.

Abstract

Background:

Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine have been found to be efficient on SARS-CoV-2, and reported to be efficient in Chinese COV-19 patients. We evaluate the effect of hydroxychloroquine on respiratory viral loads.

Patients and methods:

French Confirmed COVID-19 patients were included in a single arm protocol from early March to March 16th, to receive 600mg of hydroxychloroquine daily and their viral load in nasopharyngeal swabs was tested daily in a hospital setting. Depending on their clinical presentation, azithromycin was added to the treatment. Untreated patients from another center and cases refusing the protocol were included as negative controls. Presence and absence of virus at Day6-post inclusion was considered the end point.

Results:

Six patients were asymptomatic, 22 had upper respiratory tract infection symptoms and eight had lower respiratory tract infection symptoms. Twenty cases were treated in this study and showed a significant reduction of the viral carriage at D6-post inclusion compared to controls, and much lower average carrying duration than reported in the litterature for untreated patients. Azithromycin added to hydroxychloroquine was significantly more efficient for virus elimination.

Conclusion:

Despite its small sample size, our survey shows that hydroxychloroquine treatment is significantly associated with viral load reduction/disappearance in COVID-19 patients and its effect is reinforced by azithromycin.

Asymptomatic or Presymptomatic Infection

Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection can occur, although the percentage of patients who remain truly asymptomatic throughout the course of infection is variable and incompletely defined. It is unclear what percentage of individuals who present with asymptomatic infection progress to clinical disease. Some asymptomatic individuals have been reported to have objective radiographic findings that are consistent with COVID-19 pneumonia.10,11 The availability of widespread virologic testing for SARS-CoV-2 and the development of reliable serologic assays for antibodies to the virus will help determine the true prevalence of asymptomatic and presymptomatic infection. See Therapeutic Management of Patients With COVID-19 for recommendations regarding SARS-CoV-2–specific therapy.

COVID-19 can be diagnosed similarly to other conditions caused by viral infections: using a blood, saliva, or tissue sample. However, most tests use a cotton swab to retrieve a sample from the inside of your nostrils.

The CDC, some state health departments, and some commercial companies conduct tests. See your state’s health department website to find out where testing is offered near you.

On April 21, 2020, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the use of the first COVID-19 home testing kit.

Using the cotton swab provided, people will be able to collect a nasal sample and mail it to a designated laboratory for testing.

The emergency-use authorization specifies that the test kit is authorized for use by people whom healthcare professionals have identified as having suspected COVID-19.

Talk to your doctor right away if you think you have COVID-19 or you notice symptoms.

Your doctor will advise you on whether you should:

- stay home and monitor your symptoms

- come into the doctor’s office to be evaluated

- go to the hospital for more urgent care

Mild Illness

Patients with mild illness may exhibit a variety of signs and symptoms (e.g., fever, cough, sore throat, malaise, headache, muscle pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, loss of taste and smell). They do not have shortness of breath, dyspnea on exertion, or abnormal imaging. Most mildly ill patients can be managed in an ambulatory setting or at home through telemedicine or telephone visits. No imaging or specific laboratory evaluations are routinely indicated in otherwise healthy patients with mild COVID-19. Older patients and those with underlying comorbidities are at higher risk of disease progression; therefore, health care providers should monitor these patients closely until clinical recovery is achieved. See Therapeutic Management of Patients With COVID-19 for recommendations regarding SARS-CoV-2–specific therapy.

Acknowledgments

The Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC), an initiative supported by the SCCM and the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine, issued Guidelines on the Management of Critically Ill Adults with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in March 2020.1 The COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel (the Panel) has based the recommendations in this section on the SSC COVID-19 Guidelines with permission, and the Panel gratefully acknowledges the work of the SSC COVID-19 Guidelines Panel. The Panel also acknowledges the contributions and expertise of Andrew Rhodes, MBBS, MD, of St. George’s University Hospitals in London, England, and Waleed Alhazzani, MBBS, MSc, of McMaster University in Hamilton, Canada.

Neuromuscular Blockade in Mechanically Ventilated Adults With Moderate to Severe Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome

Recommendations

For mechanically ventilated adults with COVID-19 and moderate-to-severe ARDS:

- The Panel recommends using, as needed, intermittent boluses of neuromuscular blocking agents (NMBA) or continuous NMBA infusion to facilitate protective lung ventilation (BIII).

- In the event of persistent patient-ventilator dyssynchrony, or in cases where a patient requires ongoing deep sedation, prone ventilation, or persistently high plateau pressures, the Panel recommends using a continuous NMBA infusion for up to 48 hours as long as patient anxiety and pain can be adequately monitored and controlled (BIII).

Rationale

The recommendation for intermittent boluses of NMBA or continuous infusion of NMBA to facilitate lung protection may require a health care provider to enter the patient’s room frequently for close clinical monitoring. Therefore, in some situations, the risks of SARS-CoV-2 exposure and the need to use personal protective equipment for each entry into a patient’s room may outweigh the benefit of NMBA treatment.

Mechanically Ventilated Adults

Recommendations

For mechanically ventilated adults with COVID-19 and ARDS:

- The Panel recommends using low tidal volume (VT) ventilation (VT 4–8 mL/kg of predicted body weight) over higher VT ventilation (VT >8 mL/kg) (AI).

- The Panel recommends targeting plateau pressures of <30 cm H2O (AII).

- The Panel recommends using a conservative fluid strategy over a liberal fluid strategy (BII).

- The Panel recommends against the routine use of inhaled nitric oxide (AI).

Rationale

There is no evidence that ventilator management of patients with hypoxemic respiratory failure due to COVID-19 should differ from ventilator management of patients with hypoxemic respiratory failure due to other causes.

Cited by 1,380 articles

-

Symptomatic and optimal supportive care of critical COVID-19: A case report and literature review.

Pang QL, He WC, Li JX, Huang L.

Pang QL, et al.

World J Clin Cases. 2020 Dec 6;8(23):6181-6189. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i23.6181.

World J Clin Cases. 2020.PMID: 33344621

Free PMC article. -

Full recovery of a stage IV cancer patient facing COVID-19 pandemic.

Parmanande A, Simão D, Sardinha M, Dos Reis AFP, Spencer AS, Barreira JV, da Luz R.

Parmanande A, et al.

Autops Case Rep. 2020 Jun 5;10(3):e2020179. doi: 10.4322/acr.2020.179.

Autops Case Rep. 2020.PMID: 33344300

Free PMC article. -

A critical analysis and review of Lancet COVID-19 hydroxychloroquine study.

Toumi M, Biernikiewicz M, Liang S, Wang Y, Qiu T, Han R.

Toumi M, et al.

J Mark Access Health Policy. 2020 Sep 10;8(1):1809236. doi: 10.1080/20016689.2020.1809236.

J Mark Access Health Policy. 2020.PMID: 33343837

Free PMC article.Review.

-

.

Fogha JVF, Noubiap JJ.

Fogha JVF, et al.

Pan Afr Med J. 2020 Sep 18;37(Suppl 1):14. doi: 10.11604/pamj.supp.2020.37.14.23535. eCollection 2020.

Pan Afr Med J. 2020.PMID: 33343793

Free PMC article.French.

-

Potential Therapeutic Effect of Traditional Chinese Medicine on Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Review.

Qiu Q, Huang Y, Liu X, Huang F, Li X, Cui L, Luo H, Luo L.

Qiu Q, et al.

Front Pharmacol. 2020 Nov 9;11:570893. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.570893. eCollection 2020.

Front Pharmacol. 2020.PMID: 33343347

Free PMC article.Review.

A coronavirus gets its name from the way it looks under a microscope.

The word corona means “crown.”

When examined closely, the round virus has a “crown” of proteins called peplomers jutting out from its center in every direction. These proteins help the virus identify whether it can infect its host.

The condition known as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) was also linked to a highly infectious coronavirus back in the early 2000s. The SARS virus has since been contained.

COVID-19 vs. SARS

This isn’t the first time a coronavirus has made news. The 2003 SARS outbreak was also caused by a coronavirus.

As with the 2019 virus, the SARS virus was first found in animals before it was transmitted to humans.

The SARS virus is thought to have come from bats and was transferred to another animal and then to humans.

Once transmitted to humans, the SARS virus began spreading quickly among people.

What makes the new coronavirus so newsworthy is that a treatment or cure hasn’t yet been developed to help prevent its rapid transmission from person to person.

Thromboembolic Events and COVID-19

Critically ill patients with COVID-19 have been observed to have a prothrombotic state, which is characterized by the elevation of certain biomarkers, and there is an apparent increase in the incidence of venous thromboembolic disease in this population. In some studies, thromboemboli have been diagnosed in patients who received chemical prophylaxis with heparinoids.14-16 Autopsy studies provide additional evidence of both thromboembolic disease and microvascular thrombosis in patients with COVID-19.17 Some authors have called for routine surveillance of ICU patients for venous thromboembolism.18 See the Antithrombotic Therapy in Patients with COVID-19 section for a more detailed discussion.

References

- Yoshikawa T, Hill T, Li K, Peters CJ, Tseng CT. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus-induced lung epithelial cytokines exacerbate SARS pathogenesis by modulating intrinsic functions of monocyte-derived macrophages and dendritic cells. J Virol. 2009;83(7):3039-3048. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19004938.

- Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054-1062. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32171076.

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497-506. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31986264.

- Wang Z, Yang B, Li Q, Wen L, Zhang R. Clinical features of 69 cases with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32176772.

- Sanofi. Sanofi and Regeneron provide update on Kevzara (sarilumab) Phase 3 U.S. trial in COVID-19 patients. 2020. Available at: https://www.sanofi.com/en/media-room/press-releases/2020/2020-07-02-22-30-00. Accessed August 10, 2020.

- Le RQ, Li L, Yuan W, et al. FDA approval summary: tocilizumab for treatment of chimeric antigen receptor T cell-induced severe or life-threatening cytokine release syndrome. Oncologist. 2018;23(8):943-947. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29622697.

- Roche. Roche provides an update on the Phase III COVACTA trial of Actemra/RoActemra in hospitalised patients with severe COVID-19 associated pneumonia. 2020. Available at: https://www.roche.com/investors/updates/inv-update-2020-07-29.htm. Accessed August 10, 2020.

- Sciascia S, Apra F, Baffa A, et al. Pilot prospective open, single-arm multicentre study on off-label use of tocilizumab in patients with severe COVID-19. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2020;38(3):529-532. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32359035.

- Gardner RA, Ceppi F, Rivers J, et al. Preemptive mitigation of CD19 CAR T-cell cytokine release syndrome without attenuation of antileukemic efficacy. Blood. 2019;134(24):2149-2158. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31697826.

- Yokota S, Itoh Y, Morio T, Sumitomo N, Daimaru K, Minota S. Macrophage activation syndrome in patients with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis under treatment with tocilizumab. J Rheumatol. 2015;42(4):712-722. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25684767.

- Gritti G, Raimondi F, Ripamonti D, et al. Use of siltuximab in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia requiring ventilatory support. medRxiv. 2020. Available at: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.01.20048561v1.

Guideline PDFs

- Section Only (PDF | 492 KB)

- Full Guideline (PDF | 3 MB)

Sign up for updates

Related Content

- Guidelines Archive

- How to Cite These Guidelines

Regaining Your Strength After Severe Illness

There is much we are still learning about COVID-19, including any lasting effects on the lungs and other body organs affected. This disease has not been seen in humans before so long-term or permanent damage to the lungs is something that will be studied for years to come.

While there is still much to learn about recovering from COVID-19, experience with other types of lung infections provides medical experts with some idea of what you may expect. Your path to recovery will be unique, depending on your overall health, the treatment provided and any co-existing conditions such as COPD, asthma or another chronic lung disease.

Some people feel better and able to return to their normal routines within a week. For others, recovery will likely be slower, taking a month or more. Don’t rush your recovery. Get adequate rest and follow your doctor’s guidance on when to return to a normal routine.

Now is a great time to recommit to good health practices that keep your lungs functioning at their best, including eating healthy food, getting adequate rest and avoiding exposure to smoke and air pollution. Exercise is also important to keeping your lungs healthy. Your doctor may recommend pulmonary rehabilitation to ease back into your prior activity levels, especially if your illness was prolonged and severe.

Depending on your experience with COVID-19, the following complications may have occurred and may require additional support and recovery.

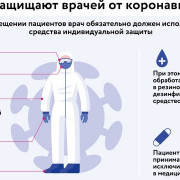

General Prevention Measures

Transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection is thought to mainly occur through respiratory droplets transmitted from an infectious person to those within 6 feet of the person. Less commonly, airborne transmission of small droplets and particles of SARS-CoV-2 that are suspended in the air can result in transmission to those who are more than 6 feet from an infectious individual. Although rare, infection through this route of transmission can also occur in persons who pass through a room that was previously inhabited by an infectious person. SARS-CoV-2 infection via airborne transmission of small particles tends to occur after prolonged exposure (>30 minutes) to an infectious person who is in an enclosed space with poor ventilation.1 The risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission can be reduced by covering coughs and sneezes and maintaining a distance of at least 6 feet from others. When consistent distancing is not possible, face coverings may further reduce the spread of infectious droplets from individuals with SARS-CoV-2 infection to others. Frequent handwashing is also effective in reducing the risk of infection.2 Health care providers should follow the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations for infection control and appropriate use of personal protective equipment.3

Panel Composition

Members of the COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel (the Panel) were appointed by the Panel co-chairs based on their clinical experience and expertise in patient management, translational and clinical science, and/or development of treatment guidelines. Panel members include representatives from federal agencies, health care and academic organizations, and professional societies. Federal agencies and professional societies represented on the Panel include:

- American Association of Critical-Care Nurses

- American Association for Respiratory Care

- American College of Chest Physicians

- American College of Emergency Physicians

- American Society of Hematology

- American Thoracic Society

- Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Department of Defense

- Department of Veterans Affairs

- Food and Drug Administration

- Infectious Diseases Society of America

- National Institutes of Health

- Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society

- Society of Critical Care Medicine

- Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists

The inclusion of representatives from professional societies does not imply that their societies have endorsed all elements of this document.

The names, affiliations, and financial disclosures of the Panel members and ex officio members, as well as members of the support team, are provided in the Panel Roster and Financial Disclosure sections of the Guidelines.

Development of the Guidelines

Each section of the Guidelines is developed by a working group of Panel members with expertise in the area addressed in the section. Each working group is responsible for identifying relevant information and published scientific literature and for conducting a systematic, comprehensive review of that information and literature. The working groups propose updates to the Guidelines based on the latest published research findings and evolving clinical information.

New Guidelines sections and recommendations are reviewed and voted on by the voting members of the Panel. To be included in the Guidelines, a recommendation must be endorsed by a majority of Panel members. Updates to existing sections that do not affect the rated recommendations are approved by Panel co-chairs without a Panel vote. Panel members are required to keep all Panel deliberations and unpublished data considered during the development of the Guidelines confidential.

Method of Synthesizing Data and Formulating Recommendations

The working groups critically review and synthesize the available data to develop recommendations. Aspects of the data that are considered include, but are not limited to, the source of the data, the type of study (e.g., case series, prospective or retrospective cohorts, randomized controlled trial), the quality and suitability of the methods, the number of participants, and the effect sizes observed. Each recommendation is assigned two ratings according to the scheme presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Recommendation Rating Scheme

| Strength of Recommendation | Quality of Evidence for Recommendation |

|---|---|

|

A: Strong recommendation for the statement B: Moderate recommendation for the statement C: Optional recommendation for the statement |

I: One or more randomized trials with clinical outcomes and/or validated laboratory endpoints II: One or more well-designed, nonrandomized trials or observational cohort studies III: Expert opinion |

To develop the recommendations in these Guidelines, the Panel uses data from the rapidly growing body of published research on COVID-19. The Panel also relies heavily on experience with other diseases, supplemented with evolving personal clinical experience with COVID-19.

In general, the recommendations in these Guidelines fall into the following categories:

- The Panel recommends using for the treatment of COVID-19 (rating). Recommendations in this category are based on evidence from clinical trials or large cohort studies that demonstrate clinical or virologic efficacy in patients with COVID-19, with the potential benefits outweighing the potential risks.

- There are insufficient data for the Panel to recommend either for or against the use of for the treatment of COVID-19 (no rating). This statement is not a recommendation; it is used in cases when there are insufficient data to make a recommendation.

- The Panel recommends against the use of for the treatment of COVID-19, except in a clinical trial (rating). This recommendation is for an intervention that has not clearly demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of COVID-19 and/or has potential safety concerns. More clinical trials are needed to further define the role of the intervention.

- The Panel recommends against the use of for the treatment of COVID-19 (rating). This recommendation is used in cases when the available data clearly show a safety concern and/or the data show no benefit for the treatment of COVID-19.

What is COVID-19?

COVID-19 is the disease caused by an infection of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, first identified in the city of Wuhan, in China’s Hubei province in December 2019. COVID-19 was previously known as 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) respiratory disease before the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the official name as COVID-19 in February 2020.

The SARS-CoV-2 virus belongs to the family of viruses called coronaviruses, which also includes the viruses that cause the common cold, and the viruses that cause more serious infections such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), which was caused by SARS-CoV in 2002, and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), which was caused by MERS-CoV in 2012. Like the other coronaviruses, the SARS-CoV-2 virus primarily causes respiratory tract infections, and the severity of the COVID-19 disease can range from mild to fatal.

Serious illness from the infection is caused by the onset of pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

Stay up to date on COVID-19

COVID-19 News (Newsfeed from Drugs.com)